8.27 Dietzgen Rosenthal Nestler Prototype

Originally posted: 2023 May 29

Some of my favorite vintage slide rules have been the early Dietzgen models with the Rosenthal scale arrangement, also referred to as a “Multiplex” rule. The Dietzgen models 1762 and 1763 from the mid-1900s, and the 1760 and 1761 in the 1910s have this scale. Dietzgen also offered its first “three cycle” scale as an option for the 1762 model in 1904-1905. Later slide rules would call this the K scale, but at that time Dietzgen designated it as E on their rules. It was first located in the well of the slide rule, but soon made its way out to the lower edge of the stock.121 Accurate reading of values in the well no doubt turned out to be difficult for the user. But the E scale in conjunction with Rosenthal’s special scale on the slide of the rule created a more efficient system for multiplying several numbers and performing roots and powers of results.

Eugene Dietzgen was sent to the U.S. at the age of 19 by his father, Joseph Dietzgen, in 1881 where he arrived in New York City. He soon began working for Keuffel and Esser (K&E) in Hoboken, New Jersey and eventually moved to Chicago after being sent to the U.S. Midwest as a K&E representative. After connecting with Otto Luhring, who was working at A.H. Abbott & Co. managing their mathematical and drawing instruments department, Dietzgen and Luhring decided to team up. They started the company Luhring & Dietzgen in Chicago to sell and promote engineering supplies on November 13, 1885. Six years later in 1891, Dietzgen bought out the shares of Luhring and started Eugene Dietzgen and Company.122

Meanwhile, also in 1891, Dietzgen’s old employer K&E had patented the “Duplex” slide rule, invented by William Cox of the U.K., which allowed quantities on the front of the rule to be keyed directly to quantities on the back of the rule. This, for example, could allow one to perform the multiplication of three numbers on the slide rule with only one setting of the slide. Since this concept was patented and not available to other manufacturers for another 17 years or so, many companies were interested no doubt in generating a set of scales that could perform this same feat on a standard “Simplex” (one-sided) slide rule design.

By 1893 Dietzgen opened his own manufacturing plant to produce T-squares, drawing boards, surveying equipment, and other relevant supplies and the company was renamed the Eugene Dietzgen Company. Then, in 1898 Dietzgen acquired a patent that was granted to John Givan Davis Mack in that year (the “Mack Improved Mannheim Simplex Slide Rule”). Mack was a professor of engineering at the University of Wisconsin in Madison.123 The Mack Improved slide rules, which have pins and springs embedded in the slide rule to maintain alignment, were a successful improvement to the general slide rule design and were sold from 1902 to 1912.

By this time frame Dietzgen and others (see the Kolesh Triplex, for instance) were looking at competitive scale layouts to improve the functionality of their slide rules.

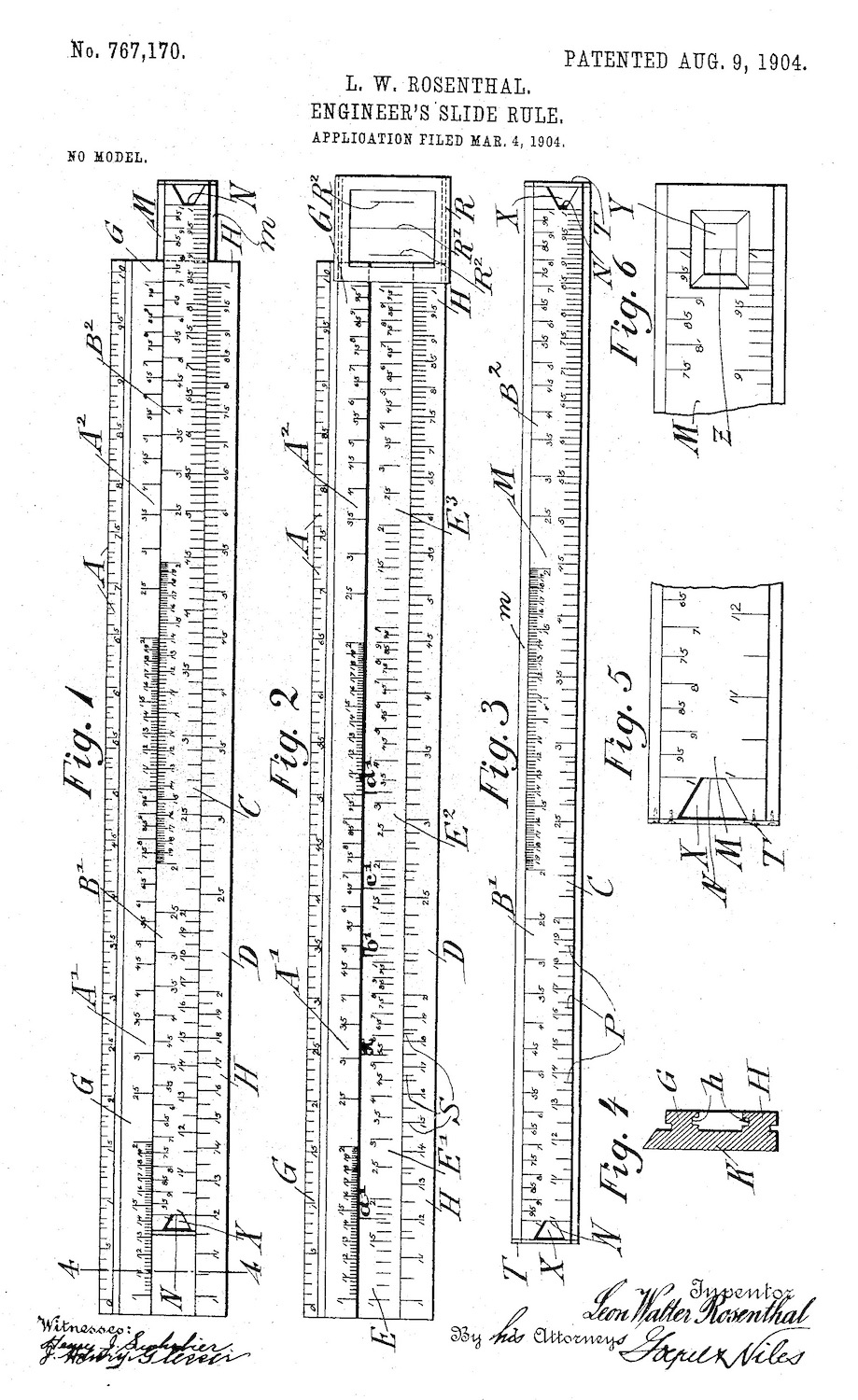

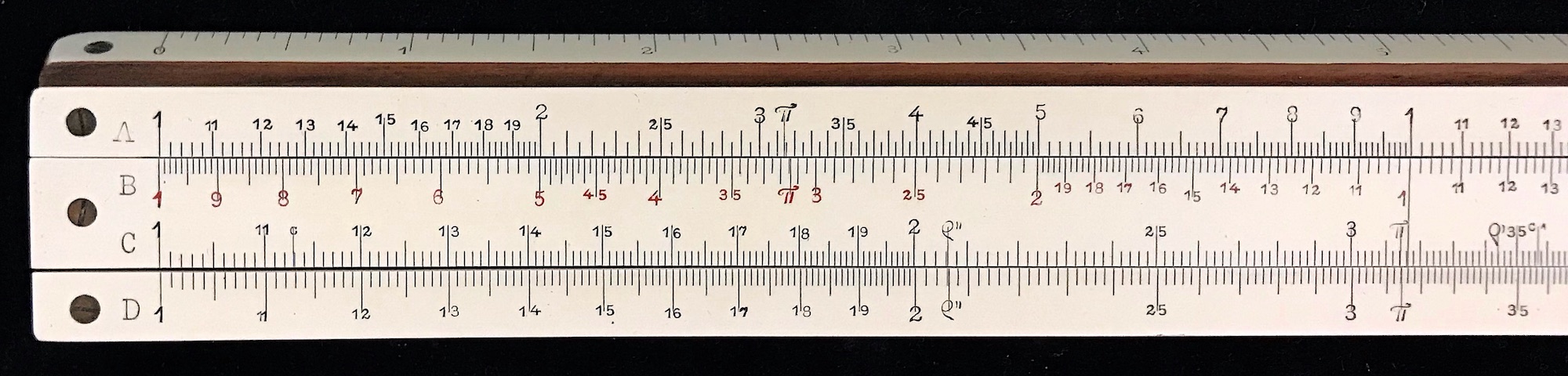

8.27.1 The Rosenthal Scale

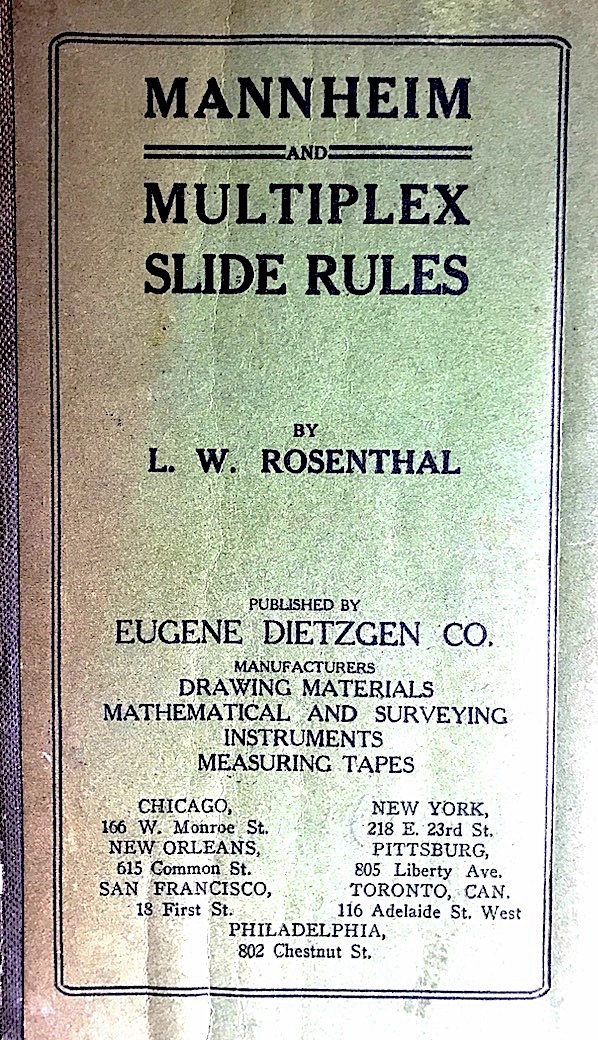

In 1904, Leon Walter Rosenthal of New York City was granted a patent for a scale arrangement with a special scale on the slide. On most slide rules the “B” scale runs from 1 to 10 to 100, or two decades, from left to right. On Rosenthal’s B scale, the numbers run, left to right, from 10 down to 1 and back up to 10 again. His patent was acquired by Dietzgen and was immediately applied to their slide rule repertoire that year with a new model, the 1762. To distinguish the two parts of the B scale, the left-side of B is called the Br scale, and the right-side of the B is called the B’’ scale. (For comparison, in the Dietzgen literature the standard A and B scales are often treated as having two parts, the A’ and A’’ scales, and the B’ and B’’ scales, each designation referring to a particular “decade”.) Below (left) is a copy of the front matter for Rosenthal’s patent of 1904. Rosenthal also wrote a book in 1905 for Dietzgen about the use of the new rule. An image of my 1911 edition is also shown below (right).

|

|

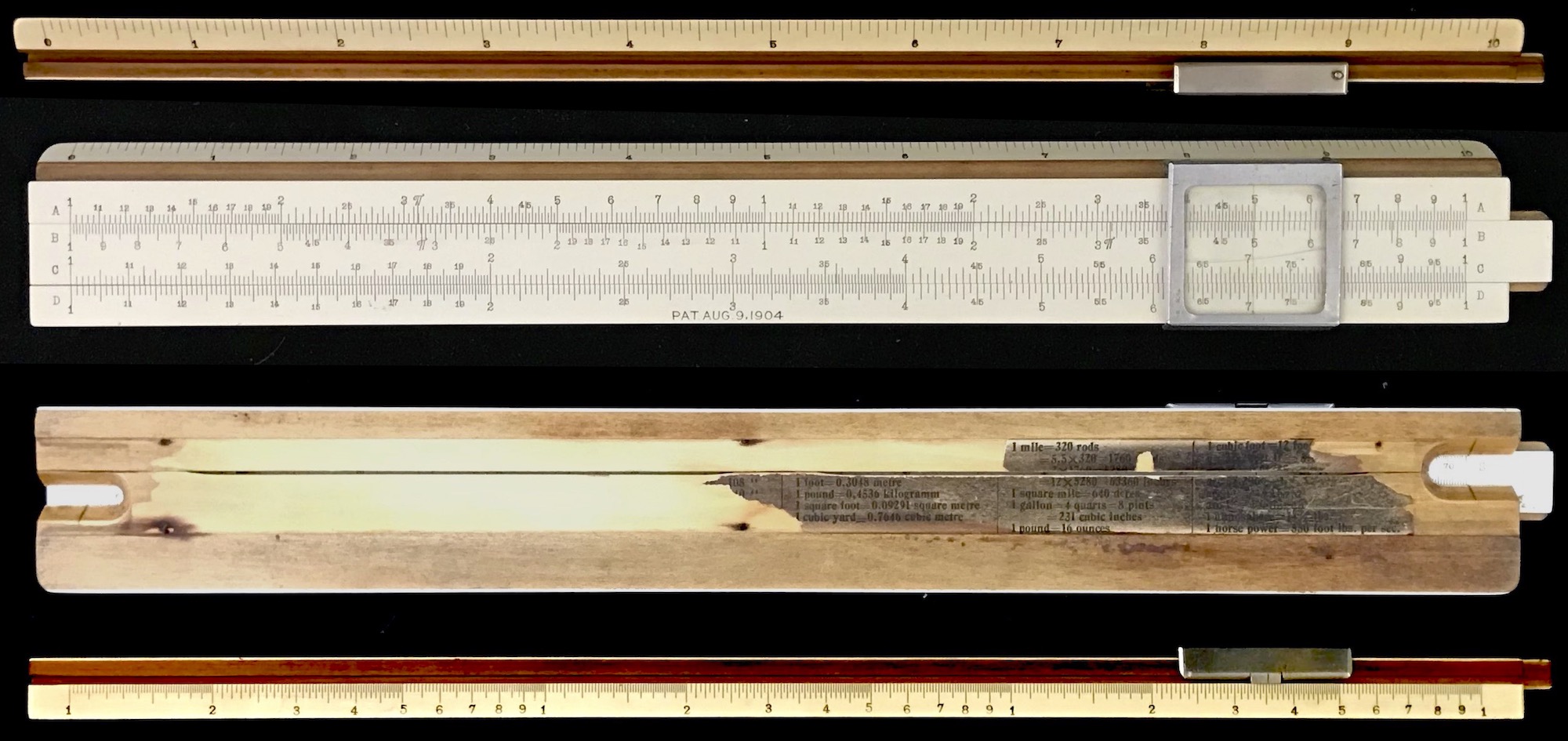

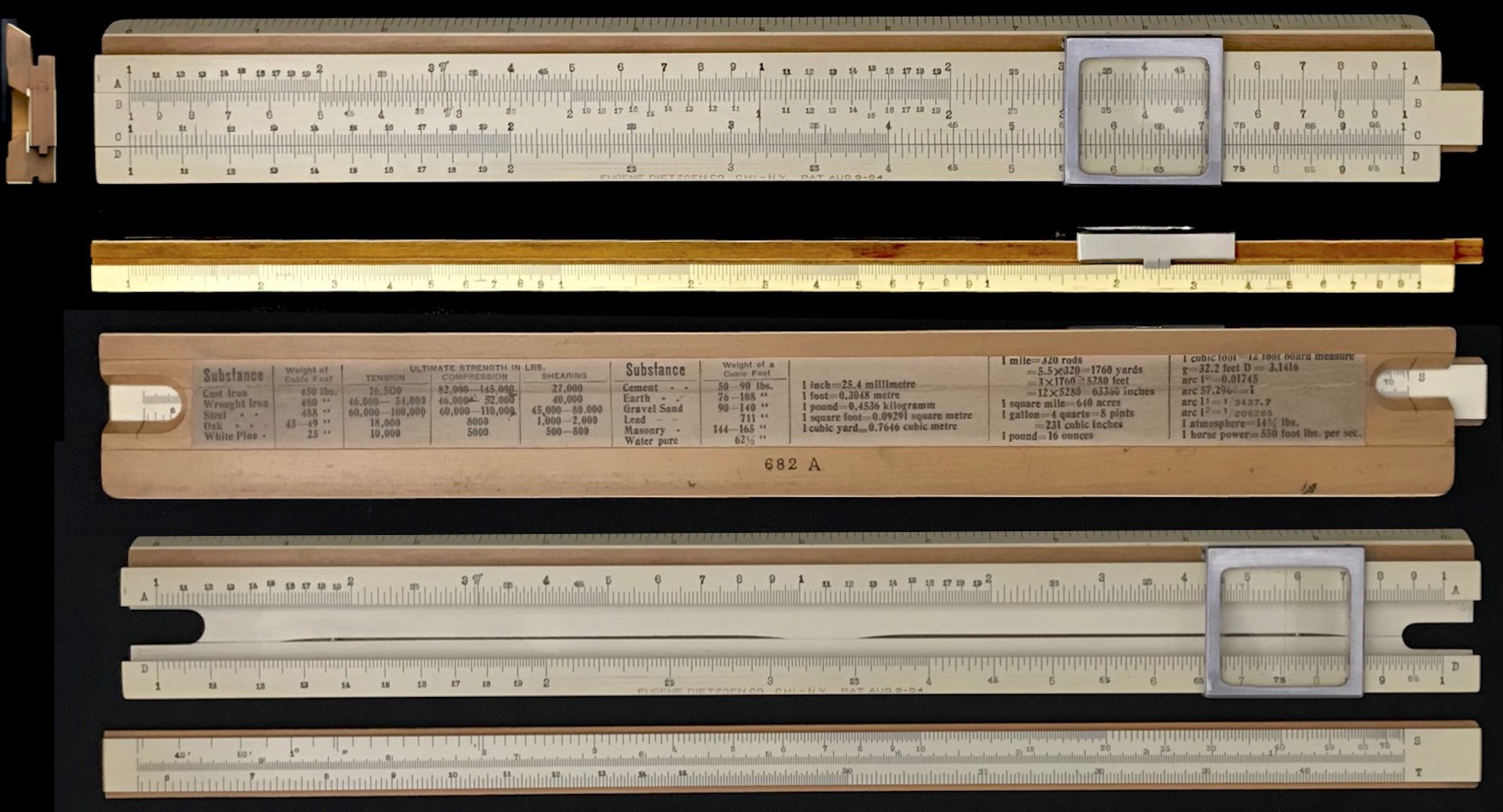

The standard Rosenthal rules in the Collection are presented in the following images. Note the special “B” scale on these rules:

| Model | Year | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1762-B |

|

1907 |

|

| 1762-B |

|

1907 |

|

| 1761-AL | 1910-1912 |

|

|

| 1760-B | 1910-1921 |

|

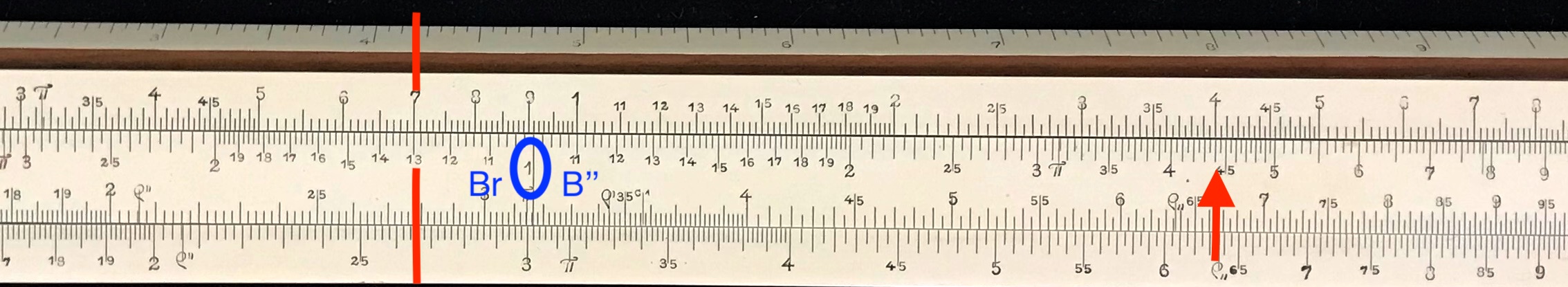

Through the use of the Rosenthal scale, one can multiply three numbers (or divide one number by two numbers, etc.) directly with one setting. For example, consider 4.4 times 7 times 13. The operation is illustrated in the image below. Since dividing by a reciprocal is the same as multiplying, we can line up 7 on A’ with 13 on Br to perform the first multiplication. The result would be on the A scale at the central index of the B scale. (In our case, 91.) Then, simply finding 4.4 on B’’ multiplies this first result by 4.4 and gives the final result on A’’: 400.

8.27.2 The Nestler Connection

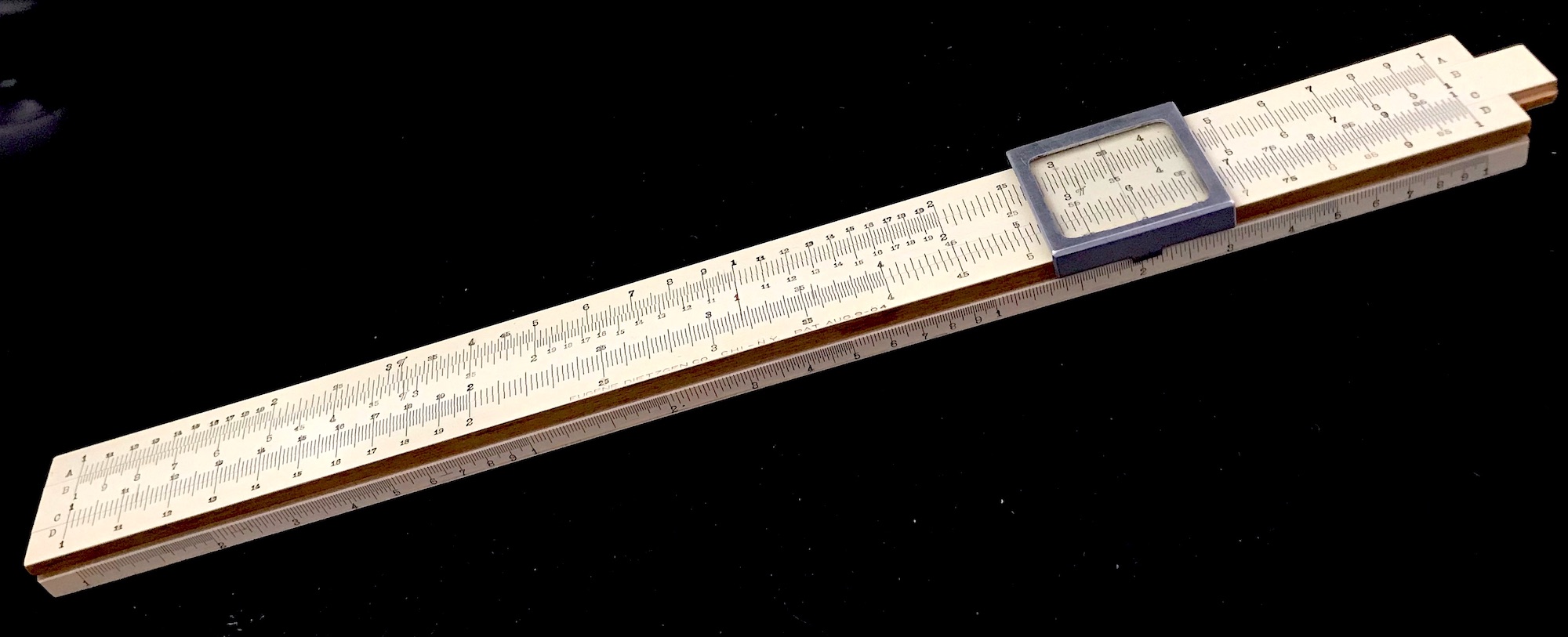

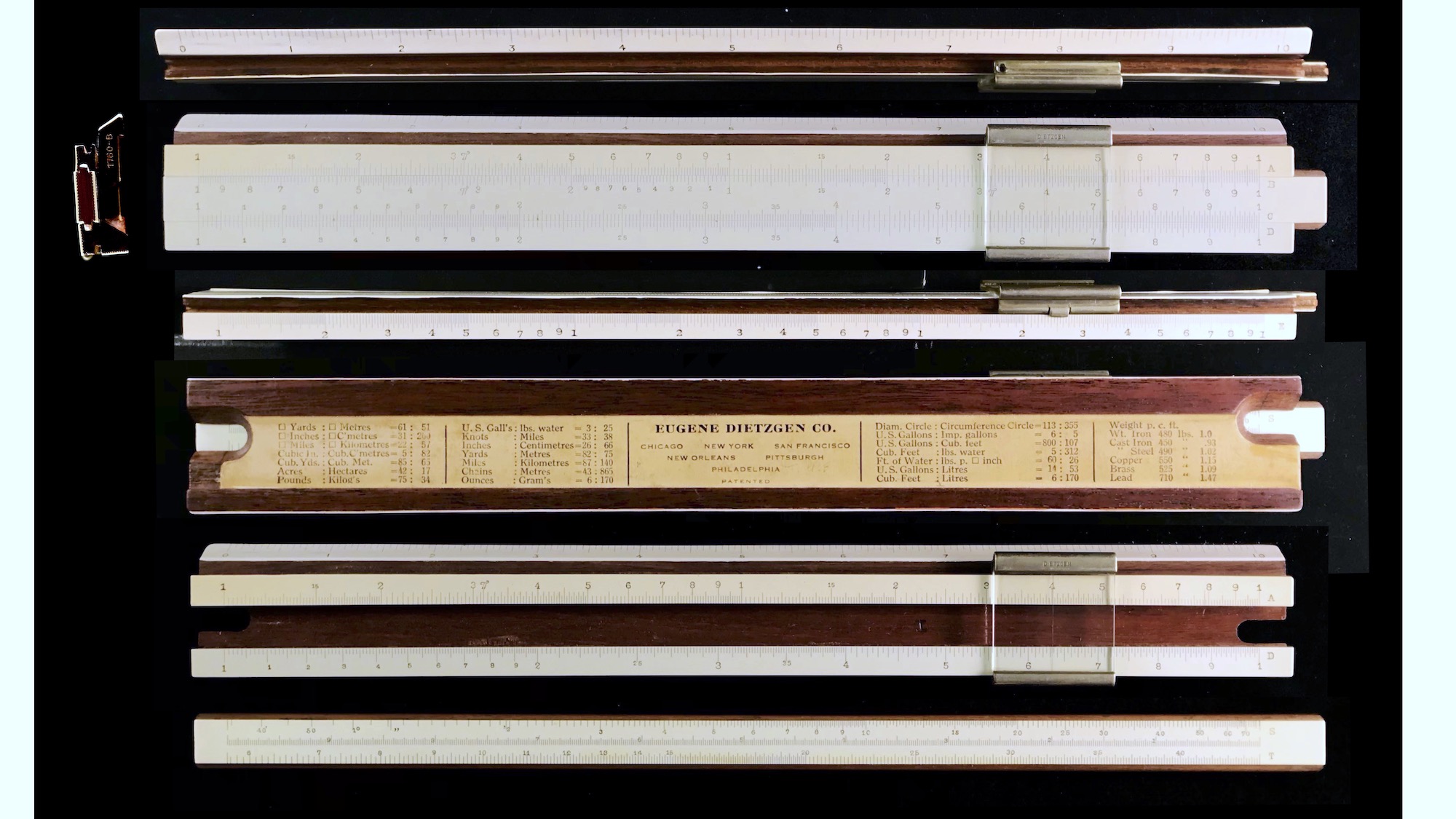

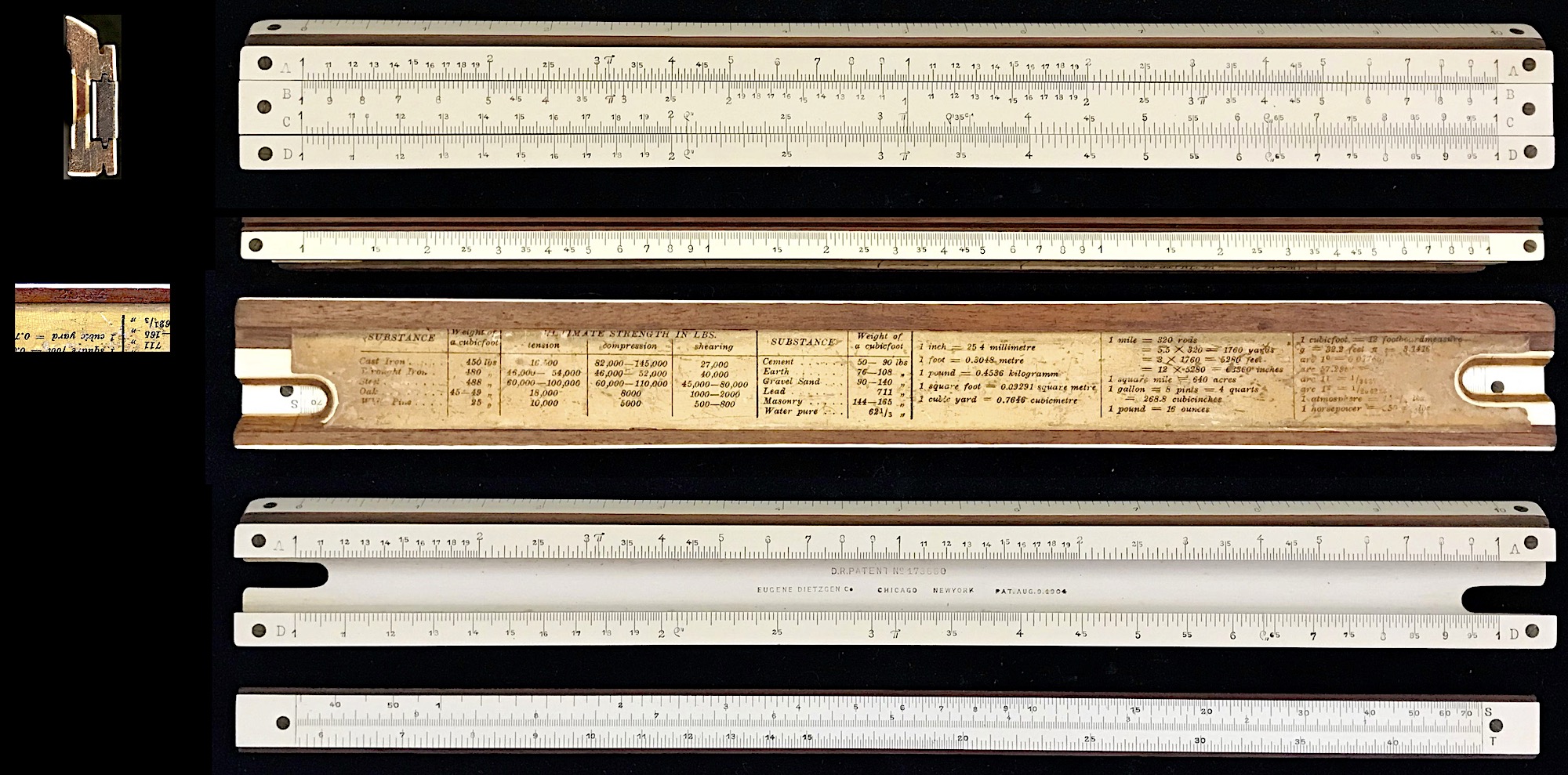

OK, now for the fun part of the story. While scrolling around in eBay one day in early 2023, I came across an ad for an early Dietzgen. It had no cursor, and was for sale for $7. At first it appeared to be a standard Mannheim type rule in the eBay picture, but what caught my eye was (a) it did not have the same profile of the other early Dietzgen rules – it looked like a German rule, possibly a Nestler; and, in addition, (b) after zooming in on the image it appeared to have the Rosenthal layout! So, I bought it.

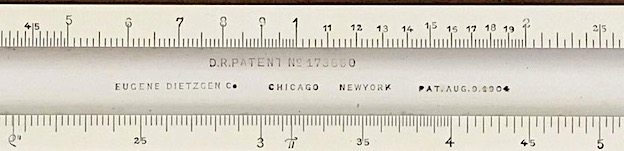

After receiving the slide rule and cleaning it up a bit, it was clearly a Nestler slide rule. In the well of the rule was D.R. Patent No. 173660, a patent granted to Nestler in 1905. On the line below that marking are the words Pat. Aug. 9, 1904 – the Rosenthal patent.

During the time frame of these patents, Nestler in Germany was the only company capable of producing engraved laminated slide rules in bulk with a short turn-around time, using their unique fully automatic dividing machine, with which any logarithmic scale could be engraved in any position and for any length.124 Using their apparatus they were known to have produced prototypes and small-batch runs for other companies, including Dietzgen. Our slide rule appears possibly to have been such a prototype. According to Craenen,125 a similar slide rule has been documented that has very similar engravings in the well and the Br scale, but also has one or two errors that evidently have been “corrected” on our prototype.

Another example of such a rule is documented in the Journal of the Oughtred Society,126 in which an example of a 16-inch (presumably Nestler) rule made for Dietzgen has the Rosenthal layout; it also has the Br scale inked in red, as does our present example.

We can definitely say that our slide rule was made in or after 1905 due to the D.R. patent on the rule. But the first Rosenthal rules were already being sold by 1905 in the Dietzgen catalog. Wouldn’t a prototype have been made earlier? As mentioned in the first paragraph of this vignette, the E scale on the original Dietzgen 1762 models was found in the well of the rule. This was later changed to be on the lower edge of the rule; this is what is seen on our prototype model. So, could it be that our Multiplex Prototype is one that was made after the introduction of the 1762 in 1905, but before the E scale placement was changed in 1907? Dietzgen would have wanted to test out the usability of the new scale arrangement before investing in a re-tooling of production equipment in Chicago.

Apparently we have one of the prototype slide rules made by Nestler for Dietzgen to demonstrate the use of the Rosenthal scale arrangement with the E scale on the lower edge. It was certainly exciting to me to have stumbled upon a prototype for one of my favorite early American slide rules, especially one with such a strong Chicago connection.

And by the way, interestingly Dietzgen did not introduce their first Duplex rules until 1941, long after the K&E patent had run out. Even though Dietzgen and others had tried to compete early on, in the long run the Duplex slide rules won the Scale Wars started near the turn of the century by K&E’s novel invention.

Rodger Shepherd, “Some Distinctive Features of Dietzgen Slide Rules”, Jour. Oughtred Soc. 5.2 p42 (1996).↩︎

Henry Aldinger, “The Dietzgen Company”, Jour. Oughtred Soc. 5.2 p40 (1996).↩︎

Guus Craenen, Slide Rules through Time, 1787-1905, https://www.oughtred.org/books/SlideRulesThroughTime.shtml.↩︎

Ibid.↩︎

Thomas Wyman, “Eugene Dietzgen’s Multiplex Slide Rule – Another Rosetta Stone Slide Rule”, Jour. Oughtred Soc. 24.1 p61 (2015).↩︎