8.25 The Scofield Engineer’s Slide Rule

Originally posted: 2024 Mar 25

In our story about Thacher’s Calculating Instrument, we noted how its inventor, Edwin Thacher, had become interested in concrete-steel construction in about 1889, which led to the construction of a famous concrete-steel arch over the Kansas River at Topeka in 1894. It is also interesting that during this period of time, Thacher had an assistant in his firm named Edson Mason Scofield. While working for Thacher, and perhaps with Thacher’s input, Scofield developed a new slide rule for use in the engineering field. An example of an early prototype/preproduction model of this slide rule was documented in 1994.102 This prototype was evidently labeled with the date September 25, 1891, as well as the phrase “Three Multiple Slide Rule.” It consisted of four logarithmic scales where the bottom scale is a reverse, or inverse, of the others. Given the time frame, this reaffirms the notion that there were Scale Wars going on in the slide rule market at the turn of the century that were interested in this particular feature of three-factor multiplication.

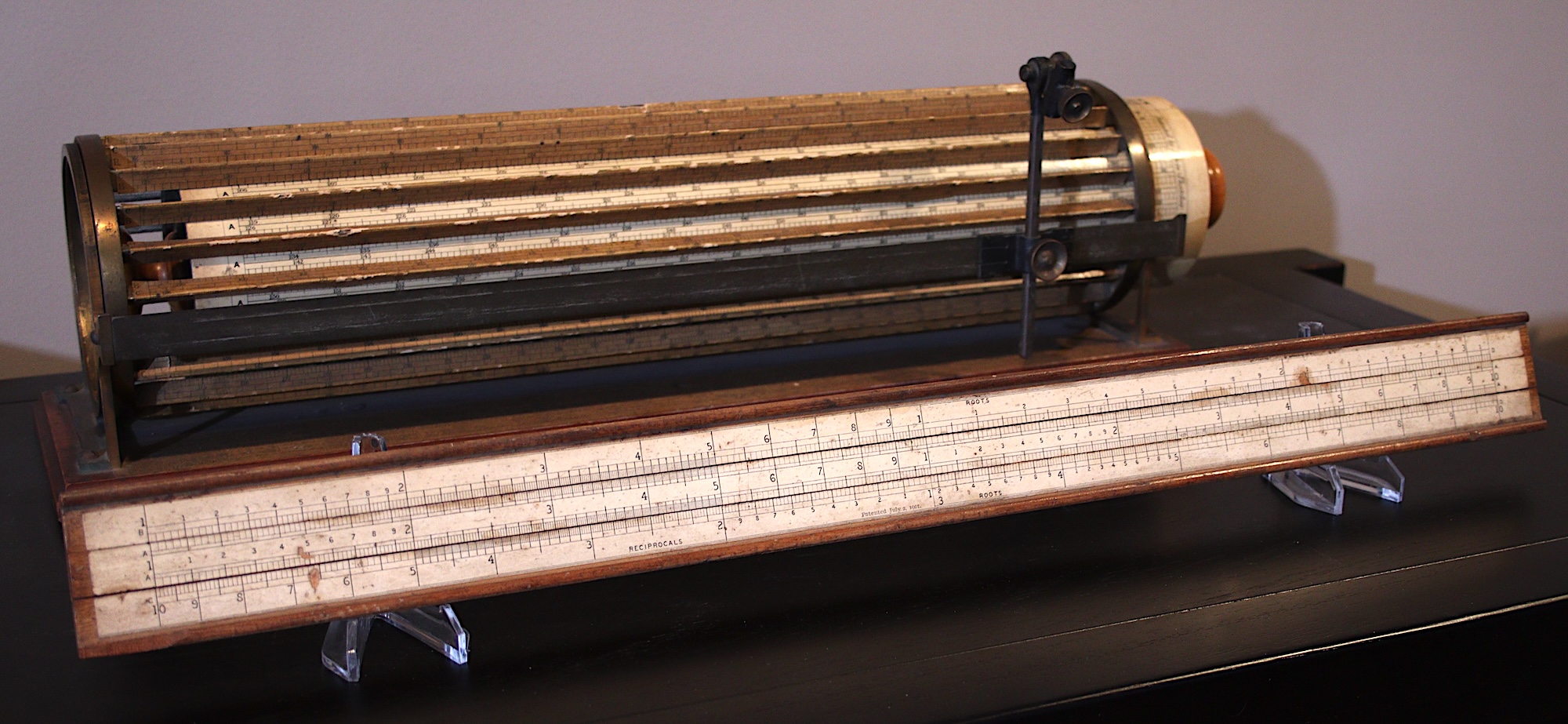

The final product, however, added a couple of other features and was eventually called “The Engineer’s Slide Rule”, an example of which was recently acquired and is displayed below:

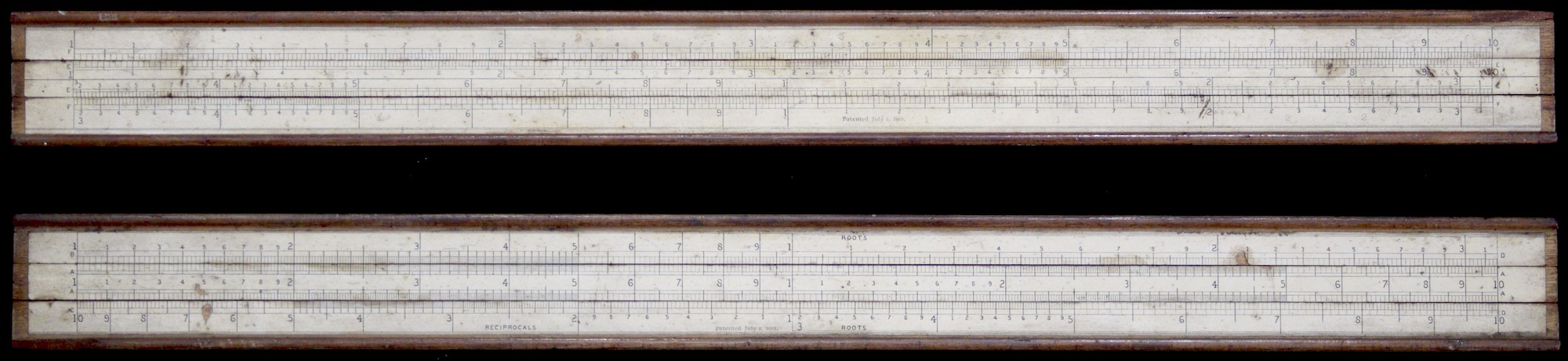

The rule has a total length of 24 inches, with 22-inch scale lengths. It is double sided with separate slides on each side (not a Duplex rule), has no cursor (by design), and has some distinctive scales. The scales are made of paper and glued upon wood, with a varnished finish. In terms of modern scale nomenclature the scales found on the slide rule are

Front: A’ _ C' [ B B ] A’I _ C''

Back: D [ C CF ] DF To be clear (hopefully), we label as C and D the longest paired single-decade logarithmic scales on the rule which can be used for standard multiplication and division. Then A and B scales would be the same length, but with two decades each. A’ refers to the first decade of an A scale, A’I refers to the inverse of the scale A’, and C’, C’’ refer to the two halves of a C scale, which correspond to square roots of values found on a B scale. The “_” indicates that the two scales (A’ and C’, for example) are found consecutively on the same line. Also, the folds of the CF and DF scales on this rule appear at \(\sqrt{10}\) and not \(\pi\).

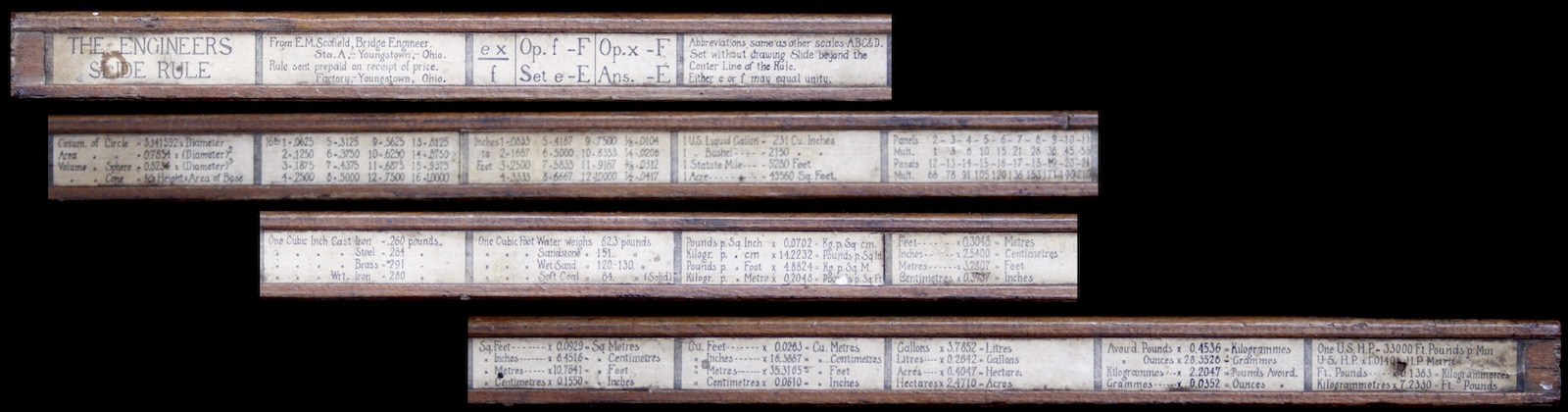

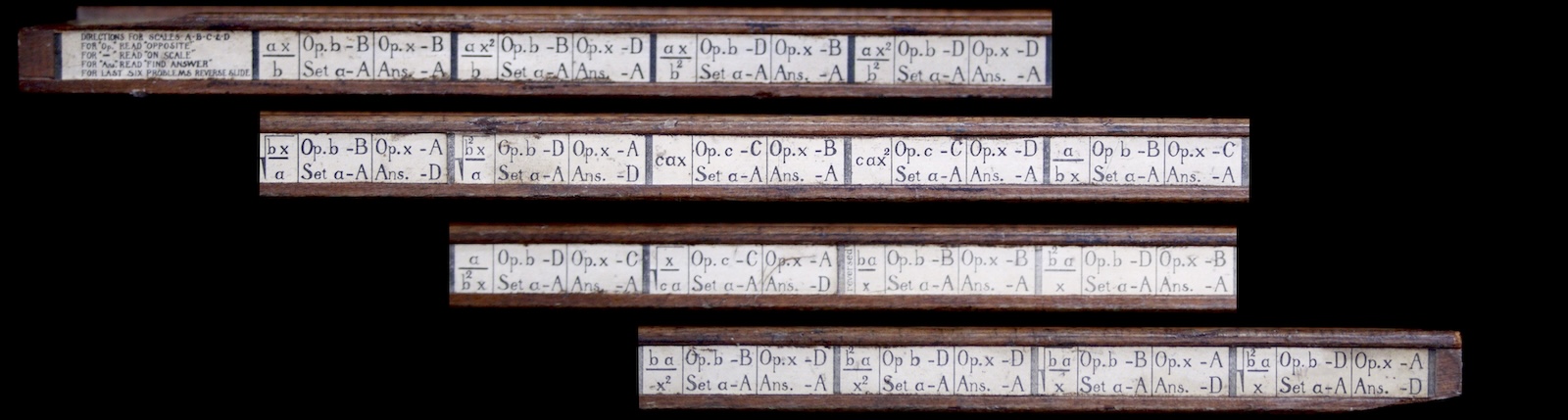

On each edge of the slide rule are 18 panels containing text. While looking at the front, the first panel on the top edge says simply, “The Engineers Slide Rule”, while the next panel gives the maker’s name as “E. M. Scofield, Bridge Engineer, Sta. A, Youngstown, Ohio.” The following two panels describe a simple calculation, while the remaining panels on this edge contain mostly tables of constants and conversion factors. The bottom edge of the slide rule has another 18 panels that describe in detail further calculations to be performed. As can be seen in the photos below, the directions given for using the slide rule are akin to the standard use of proportions as was discussed in the Carpenters vs. Engineers vignette. These features, along with its cursor-less design, indeed classifies it somewhat along the lines of the Engineer’s rules of the early 1800s, though with more functionality.

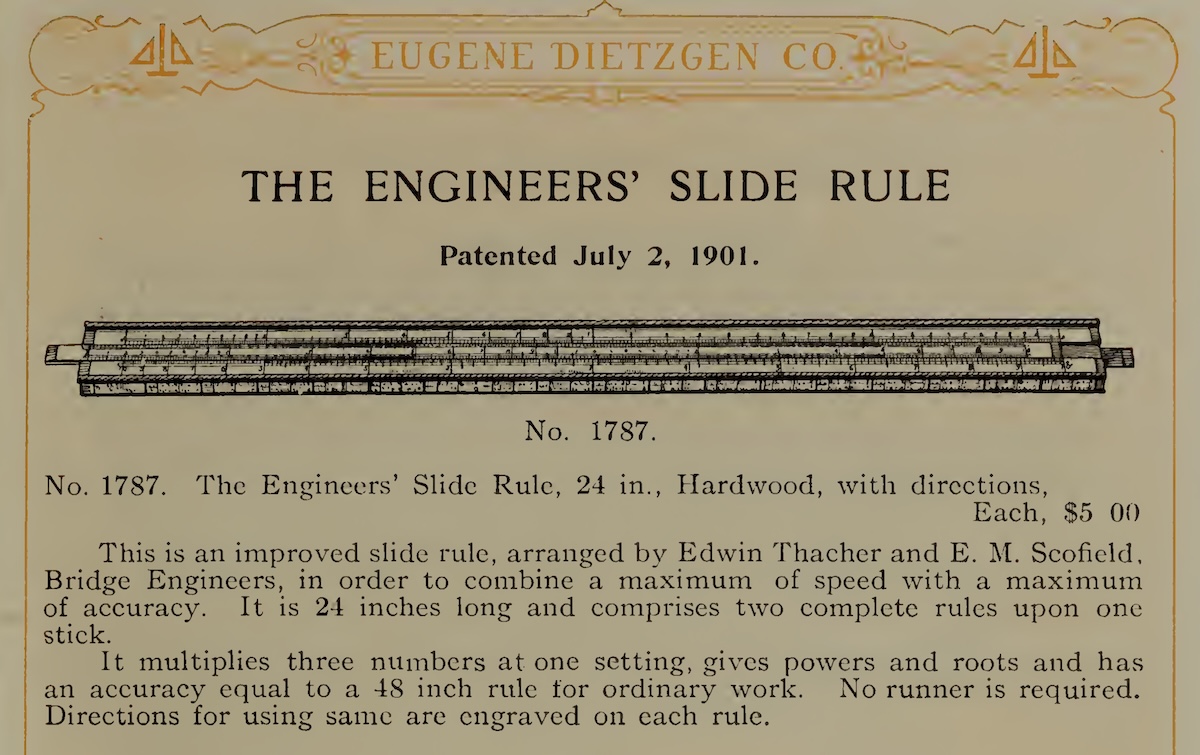

Although Scofield created his prototype rule in about 1891, the concept that became the Engineer’s Slide Rule was patented in 1901, and that was submitted and acquired by none other than Thacher. It is in this year, apparently, that production of the Engineer’s Slide Rule began. In the second top panel are also the words, “Rule sent prepaid on receipt of price” as though the rule could have been ordered through Scofield and might have been sent in the mail by Scofield himself. However, it is well known that the slide rule was sold by Dietzgen out of Chicago, and only Dietzgen. Dietzgen catalogs listed the rule from 1904,103 if not earlier, until at least 1931. It is not known if Scofield intended to sell it himself and then gave the process over to Dietzgen, or if they both sold the rule simultaneously. The rule was relatively cheap, roughly one third to one quarter of the price of the fine wood and celluloid-laminated slide rules being produced at that time. The following listing can be found in a variety of Dietzgen catalogs from this era, this one being from 1907:

Note that Dietzgen’s 20-inch Multiplex (Rosenthal) Rule was selling for $15 in the same catalog.

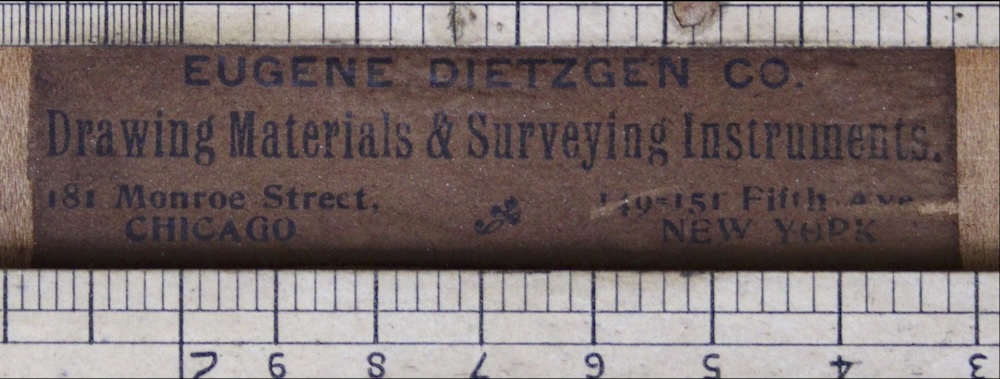

Dietzgen expanded its operation, which was formed in Chicago in the 1880s, to include offices in New York starting in 1897, San Francisco in 1902, and New Orleans in 1903. Offices in other cities were added later. When either of the slides on our Scofield slide rule is removed, a Dietzgen sticker can be found on the left end; an image of one is shown below. (Both stickers under the slides are identical.) Since only Chicago and New York are listed, this indicates that the rule was most likely fabricated in 1901. The exact year in which it was sold is a different issue. One also finds match numbers marked in pencil on the right ends of both slides, as well as on the stock under the slides, for matching parts during manufacturing.

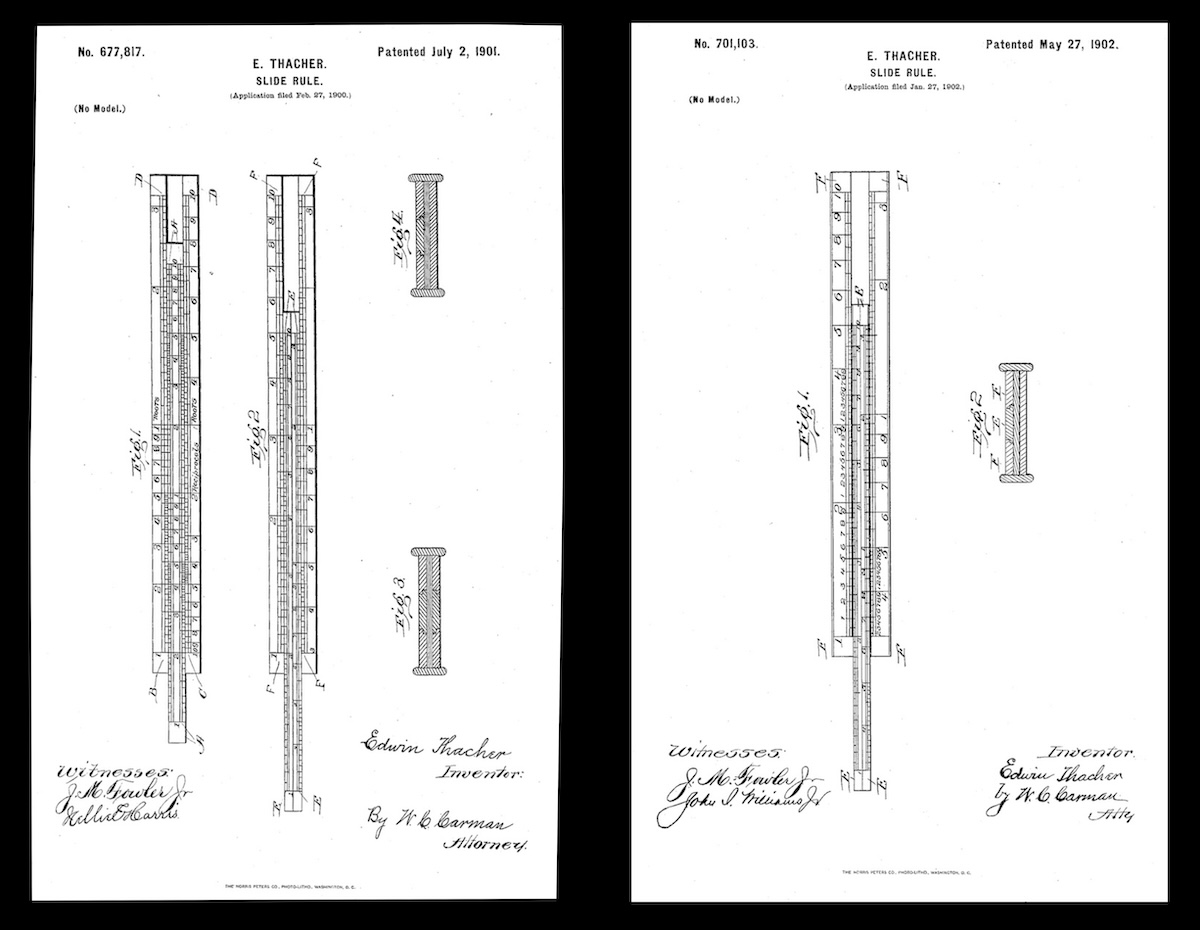

Both sides of the slide rule show the words, “Patented July 2, 1901.” Examining the text of the patent itself, we find that Thacher claims it to be his invention, but the author information on the front page reads, “EDWIN THACHER, OF PATERSON, NEW JERSEY, ASSIGNOR OF ONE-HALF TO EDSON M. SCOFIELD, OF YOUNGSTOWN, OHIO.” The text describes the scales and construction of the slide rule shown above (not the pre-production model), and discusses its use in calculations, many of which are also depicted in the images on the edges of the slide rule. One can imagine that most of the text on pages 2 and 3 of the patent would comprise the instructions that may have come with the slide rule.

There was a second, related patent issued to Thacher, again with one-half assigned to Scofield, this one in 1902. This patent describes a slide rule with a single side on which there are four scales – the top scale on the stock is a logarithmic scale from 1 to 10, as is the top scale on the slide, whereas the bottom scales (slide and stock) are logarithmic scales that begin and end at \(\sqrt{10}.\) In other words, in more modern terminology, the scale set could be designated as

D [ C CF ] DF

although most modern CF/DF scales are folded at \(\pi.\) Thus, the 1902 patent is essentially for the arrangement of the back side of the Scofield slide rule. But it goes further than that. In the summary of the patent application, one of Thacher’s claims is that his new invention includes

- A slide-rule bearing two duplicate logarithmic scales relatively fixed, and so arranged that the square root of the base system of logarithms in one scale is approximately opposite the unit of the other scale, substantially as described.

What I find very interesting in this paragraph are the use of the words “square root of the base” (note, it need not be 10!) and the statement that the starting point need only be “approximately opposite the unit of the other scale,” the word “unit” referring to the “1” on the other scale. That is, for example, if the folded scale starts at \(\pi\) (= 3.142) then the square root of the base, \(\sqrt{10}\) (= 3.162), would be nearby and thus covered by the patent. Clearly Thacher’s main point in applying for the eventual 1902 patent was to clarify this particular point.

Coincidentally, perhaps, the folded scales on Keuffel & Esser slide rules appeared first on their pricey Model 4090 Universal Slide Rule in the 1901 catalog (and on the 16 inch version, the even pricier Model 4091, in 1906). The folds occurred at \(\sqrt{10}.\) In 1913, however, K&E introduced the Model 4088 series which included CF and DF scales, folded at \(\pi,\) and the Universal rules were retired. It begs the question as to whether Thacher knew of this impending development of having folded scales at \(\pi\) and felt the need to quickly patent the idea, and/or whether he – as the one who introduced the general concept in his Calculating Instrument, which was sold by K&E – might have had some guiding influence on K&E’s directions in this matter.

Another bit of interesting information is that an example of a Scofield slide rule recently appeared for sale on eBay that had both patents present on the face of the rule, on the side with the relevant four scales. It reads, “Patented July 2nd, 1901, and May 27th, 1902.” The layout of the scales on this rule is the same as that found on the Scofield in our image above, including the fact that the fold occurs at \(\sqrt{10}.\) For me, this is the only Scofield I have seen thus far with both patents mentioned. These are, after all, fairly rare slide rules so I haven’t seen all that many. (And of course the only one I’ve seen directly in front of me is the one I now own.) But I wonder if a very large batch of “1901” rules was produced in that year and sold over many years and then, later, when a new large batch was required, both patents were then shown on the rule, meaning that the double-patent Scofields may have been manufactured very much later than 1902. The fact that our rule does not have the 1902 patent, along with the existence of the Dietzgen sticker, gives support to the proposal that our rule was indeed produced in 1901.

Let’s review – we have Scofield’s “Three Multiple Slide Rule” prototyped in 1891, the same year that K&E acquired the patent for the Duplex slide rule concept. We have the Scofield-Thacher rule patented in 1901, the same year that Thacher moved from the midwestern US to New York City to work with William Mueser in his Concrete Steel Engineering Company. This was also the same year that the Universal Slide Rule was first exhibited in the K&E catalog with folded scales included. And Thacher immediately applies for a more general patent – awarded in 1902 – regarding folded scales when he, or someone, realized that the square root of 10 is almost \(\pi\) and that the engineering world would surely prefer having the latter as a fold point.

So it seems to me that the Scofield-Thacher Engineer’s Slide Rule and the associated patents played non-trivial roles in the development and timing of the folded scales found on future slide rules such as those developed by K&E. The fact that a separate 1902 patent was generated for scales that had already been implemented on the Scofield-Thacher rule since 1891 and patented in 1901, leads me to believe that Thacher was already thinking ahead about what new options were in the pipeline for K&E, Dietzgen, and other manufacturers. And with K&E selling the Thacher’s Calculating Instrument while Dietzgen was selling the Scofield-Thacher Engineer’s Slide Rule, Thacher and Scofield had the bases covered during the period of the early Scale Wars.

Below are images of the figures found in the two patents.

Whatever patent wars may have been going on, or not, it is interesting that Dietzgen continued to sell the Engineer’s Slide Rule – “arranged by Edwin Thacher and E. M. Scofield, Bridge Engineers” – for approximately three decades without significant changes to its design or construction. The only change I have seen so far is the addition of the second patent on the face of the rule. Were these slide rules kept “cheap” so as to be more adaptable to work in the field, where damage to the rule could be tolerated and new rules purchased as needed? The fact that it did not need to have a cursor may have been a desirable feature in such circumstances. There must have been a fair amount of inventory, having been sold for over 30 years, yet these rules are apparently relatively rare. Perhaps they were purposefully thought of as expendable and as a result simply were not saved by the ones that used them. Or perhaps sales were slow, but Dietzgen just kept a large stock of original 1901 items in their inventory until they eventually sold them all, simply giving the item space in their catalog each year. And did K&E have a special arrangement with these gentlemen that allowed K&E to go forward with their “\(\pi\)” folded scales within the usual 17-year U.S. patent window? In any event, the Engineer’s Slide Rule apparently provides a significant linkage between the standard Mannheim scale set and the barrage of new scales that were to be introduced to slide rule users during the ensuing decades.

As for Scofield himself, in 1903 he and his brother, Glen M. Scofield, founded the Scofield Engineering Construction Company in Philadelphia. Fifteen years later he expanded his operation to San Diego, and then to Los Angeles in 1920, moving to LA that same year. His company’s noteworthy LA construction projects included the Biltmore Hotel, the United Artists Theater, the Pacific Finance Building, the Pershing Square Building, and the Pacific Mutual Building, to name a few.104 He died in Los Angeles in 1939.